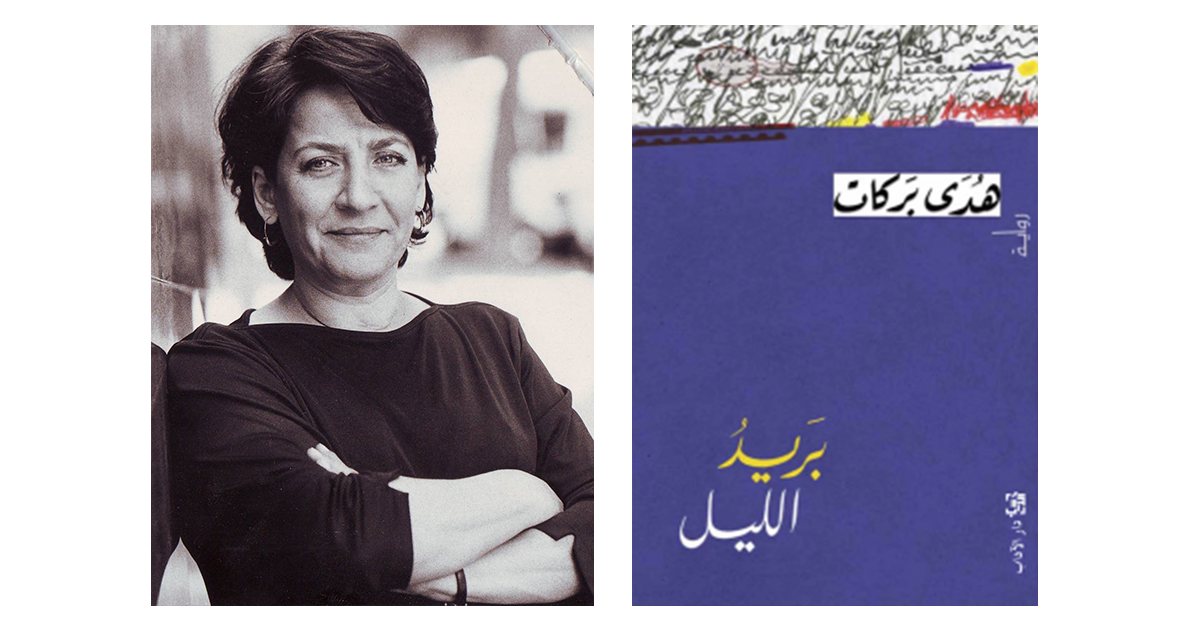

Interview with shortlisted author Hoda Barakat

15/03/2019

Where were you when the shortlist was announced and what was your reaction?

I was in my house in Paris and I heard the news from my publisher Rana Idriss (Dar al-Adab). I was happy of course. Then I got involved in arrangements for the tiring journey from America to Abu Dhabi.

When did you begin writing The Night Mail and where did the inspiration for it come from?

I began writing it four years ago, but it changed a great deal and I was constantly re-writing. I chose its final form when scenes of migrants fleeing their countries had ceased to fill my imagination. Those people who have lost their homes and are scattered over the earth, fleeing wars, poverty, terrorism and dictatorship, especially from our Arab region. They board boats of death and the world doesn’t want to look at them, other than as an unwanted mass, or a virus threatening civilisation. At this time, we are seeing a regression in the humanitarian dimension of those civilisations, as countries protect themselves by closing their doors.

This doesn’t mean that I want Western countries to fling open their borders or to look on those fleeing as angels. I just wanted to listen to the lives of wanderers through the desert of this world.

Did the novel take long to write and where were you when you finished it?

I began writing it in my house in Paris. Then I re-wrote it, firstly in a writing residency in Brussels, and I completed it in another residency in Budapest. In Paris, there was the stage of “pruning” until it emerged in its final form.

In a previous interview, you said that the characters of The Night Mail experience “an extremely complicated form of exile, new for us”. Could you comment on that?

Their exile begins with where they have come from, their countries, and does not end in the places they pass through, nor the ones where their journey stops, since their goal is not to stay there. There are no places nor journeys of exile. Their travelling resembles neither this nor that. They pass over the earth as no people have done before, at least in recent history.

The characters write five letters, knowing they will not arrive. Does The Night Mail deal with a crisis in communication, since – as you have also said – “we can no longer read this age well, nor each other”?

Yes, that’s right, the letters are written without hope that they will reach their recipients. Sometimes they do not have a beginning or end, an address or a signature. The words of the letter or its contents are not necessarily a true and sincere confession. The letter is a moment where its writer stops and contemplates a dark night…

We are not good at reading the time we live in. We are not good at engaging with it nor standing against it. Our peoples are doomed to subservience or blind violence. It is a time of great perplexity and… sadness.

The novel does not issue moral judgments on its solitary, alienated characters, despite the fact that they are problematic. Rather, it inspires pity for them. Do you consider that the characters are victims of political circumstances first and foremost, or of society, or something else?

No, the novelist’s job is not to issue judgements, moral or otherwise. Listening to the weak, lost or wronged voice is in itself a moral work. Writing about our anxiety and perplexed lives is perhaps what gives a moral dimension to writing. Before making a moral judgement, we need to listen and try to understand. The characters of The Night Mail are not completely innocent victims and I am not writing to make them so. They are a blend of what their countries and societies have made them and so they are ensnared in their sicknesses; but I wanted the murdering jailer, for example, at a particular moment of his life, to write a letter to his mother, crying and listening to Fairuz, and so we learn something of his life and see a little of its complications, without trying to exonerate him…

How can we “read each other well” and does this novel help us to do that?

I hope that this novel, somehow or other, will have given voice to brittle lives, which are judged by others without understanding them or investigating what brought them to their current state.

I also hope that I have conveyed something of the quality of the voices of these strangers to whom no-one, in general, listens.

What is your next literary project after this novel?

It’s another novel, of course.

Incidentally, I hope that Arab writers living in the West will be invited to more literary residences in Arab countries.